I’m reading Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag (2007) as part of my education in ideas about the abolition of prisons and police. Gulag is a book about California’s prison system, but it expands to cover broadly what abolitionists refer to as the carceral state.

I started my abolitionist education with Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete? (2011), but read that book before I started taking serious notes for this slipbox. After Gulag, I’ll read Vitale’s The End of Policing (2017). Because I have an eleven-year-old daughter, a romantic partner, a day job, and many other extra-curricular interests, this education will take a long time, probably a full year, maybe more than that. I think that’s okay, because it will probably take a long time for abolition to happen if it ever does (a delay that might not be okay). Even if abolition never happens, it will take a long time for any other meaningful reform to happen, as well, even if people keep righteously burning down corrupt police stations and standing up to an increasingly authoritarian police state.

Within my abolition education, this slipbox note starts a thread that describes in the language of causal diagrams the competing narratives about American incarceration. Meanwhile, it wrestles with sociologist Mo Torres’s (2020) suggestion that those of us new to the abolition literature read it from the position that a better world – a world that in Torres’s view includes prison and police aboltion – is possible. God damn it, it’s so hard right now to believe that a better world is possible. But I’m trying.

Anyway, let’s get started.

I’ll begin on page seven of Gilmore’s introduction, where she points out that California’s prison system expanded rapidly between 1982 and 2000 even though crime in California peaked in 19801. Gilmore is clearly asking why California started building more prisons even as its crime rate declined. Yet right here on one of the first pages of Gilmore’s introduction is where I began to realize how difficult it would be to take Torres’s advice.

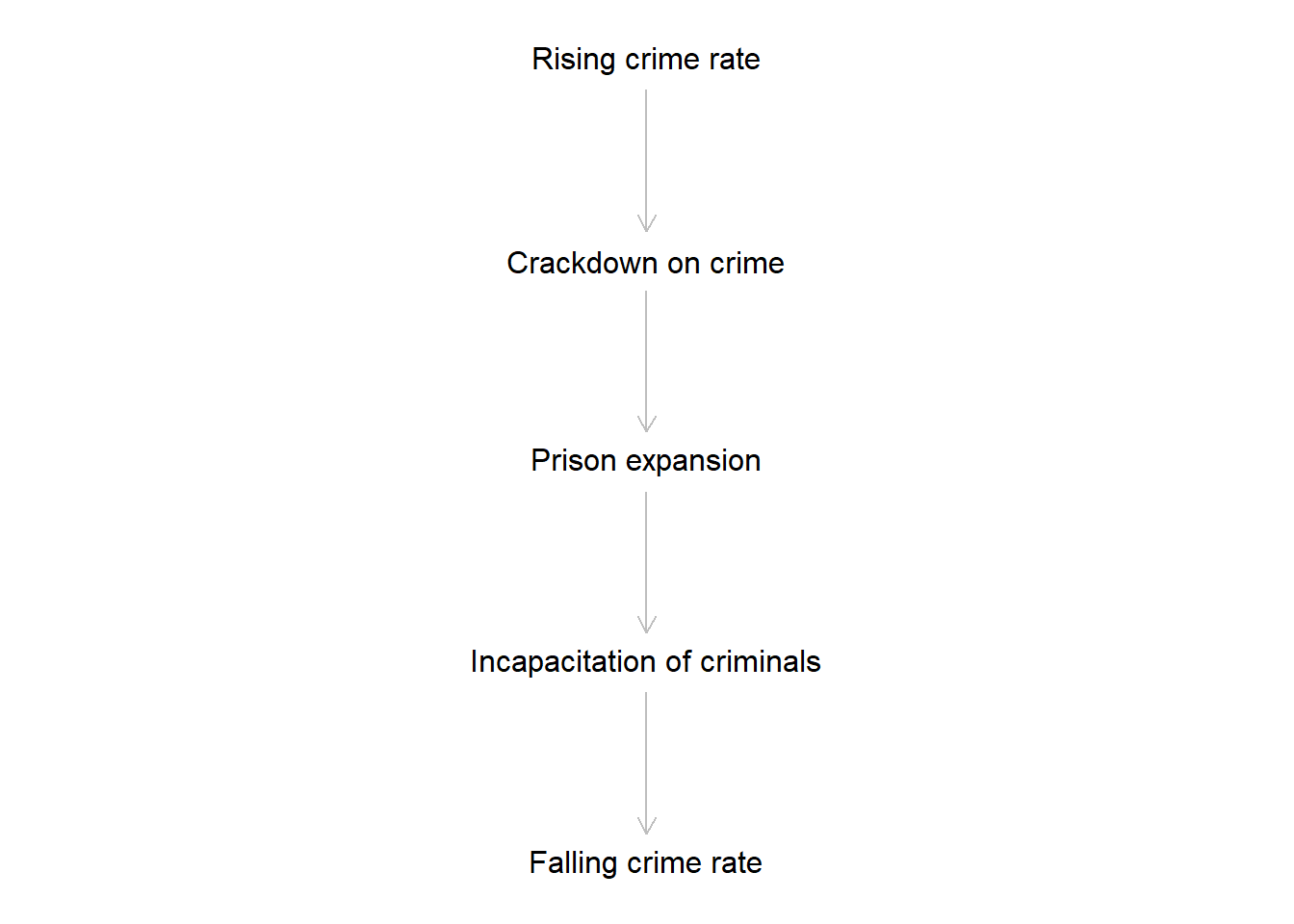

My first thought upon reading Gilmore’s description of California’s history above was: Wait, doesn’t that timeline support rather than refute the effectiveness of the carceral state? The proponent of the carceral state would say: Crime rates rose from the 60s into the 80s, and we responded by throwing more and more people into prison. As the result of incapacitating criminals (i.e., removing them from society and locking them in cages where they can’t commit crimes), crime went down. Thinking about this simple counterargument, I thought: Doesn’t opening your book with this timeline (as Davis’s book also did) leave the abolition movement vulnerable to swift rebuttal?

The argument in favor of criminal incapacitation through incarceration is compelling because it is simple, but also because it matches the timeline. If you think the argument isn’t compelling, you haven’t been paying attention; millions of Americans are convinced by it, even the ones who understand the trajectory of crime rates in the 20th and 21st centuries.

I’ll illustrate the simplicity of the causal argument in favor of incarceration by drawing a causal diagram. The circles in the diagram represent facts. The arrows point from causes to effects. The fancy scholarly term for this type of diagram is “directed acyclic graph” or “DAG”. You can use the dagitty package in R (Textor and van der Zander 2016) to draw one of these bad boys.

library(dagitty)

carceral_dag <- dagitty::dagitty('dag {

"Rising crime rate" [pos="0,1"]

"Crackdown on crime" [pos="0,2"]

"Prison expansion" [pos="0,3"]

"Incapacitation of criminals" [pos="0,4"]

"Falling crime rate" [pos="0,5"]

"Rising crime rate" ->

"Crackdown on crime" ->

"Prison expansion" ->

"Incapacitation of criminals" ->

"Falling crime rate"

}')

plot(carceral_dag)

It’s as simple of an argument as that. I think a fifth grader could figure this DAG out.

Now if you’ve read this far and concluded that I am myself a proponent of incarceration, you’d be wrong. I am strongly committed to studying prison abolitionist ideas and advocating for them if I become convinced. I am also already convinced that most non-violent crimes – especially crimes related to drug use and sales – shouldn’t lead to prison time. I’m also strongly committed to encouraging my friends and family to educate themselves about abolition, too. I mean, fuck, dude, I bought my own mother a copy of Are Prisons Obsolete? from a Black-owned book store. I’m not patting myself on the back. I’m an affluent White dude who was sired by a moneyed descendant of slaveholdrs, and who works for a large corporation; so fuck patting myself on the back. I’m just trying to assuage your fears that you’re reading the diatribe of a thin blue line walking asshat.

Anyway, as we’ll see, the simplicity of the carceral DAG is part of the problem. We will, with Gilmore’s help, interrogate the merits of that DAG. Moreover, we will invoke Gilmore’s arguments to confront the carceral DAG with convincing causal narratives about the negative impact of incarceration on communities. We will even use causal narratives to entertain the possibility that abolition might be the right choice even if incapacitation is an effective means of lowering the crime rate.

More later on the controversy over when the peak happened↩︎